Below is my documentation of one of my competition pieces earlier this year. I got side tracked by other projects and will be posting an update later with the finished cuffs. Currently I have 1 cuff 3/4 of the way done. Wish me luck and happy reading.

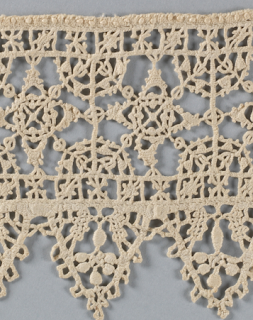

Punto in Aria Lace Cuff

The Honorable Lady Isabelle de Calais

Kingdom Arts and Science Competition 2019

Punto in Aria Cuff from late 16th Century Venice

During the 16th century intricate lace work became increasingly popular. With the increase in popularity the methods of creating laces diversified to include plaited laces such as bobbin lace, and needle-based laces such as punto in aria and reticella. These laces could be added to linen undergarments and housewares. One of the most popular uses for lace in this period was on accessories such as veils, handkerchiefs, ruffs, and cuffs.

Making the Lace

Pattern Books vs. Professionals

It is easy to assume that all lace was made by professional artificers in a shop. In mid 16th century Florence the velettai (veil makers) would often make handkerchiefs and veils edged in needle made laces (Landini 2011). When using a professional, there may be tighter stitches or the opportunity for a unique pattern to be created.

Something that many history books forget is the number of publishers producing pattern books all over Europe during this period. Pattern books for lace and embroidery were marketed towards women of leisure to keep them out of trouble. Vinciolo has a sonnet in his book, Singuliers et Nouveaux Pourtraicts, dedicating the works to them for their use. While it was originally printed in 1587, it would go through at least 10 more reprints across France and Italy over the next 30 years. Below is a translation of the dedication sonnet, originally in French, by Elsa Ricci:

One man will strive to win the heart of some liege lord

In order to possess a sum of riches great;

Another in high rank himself would situate;

Another in wars will seek for his reward.

But I who only seek to keep from being bored,

Am satisfied to live in this my lowly state,

And by my labors gave strive only to create

A gift for womankind, contentment to afford.

Then, ladies, please accept (I pray you will so do)

These patterns and designs I dedicate to you,

To while away your time and occupy your mind.

In this new enterprise there’s much that you can learn

And finally this craft you’ll master in your turn.

The work agreeable, the profit great you’ll find

To die unremittingly for virtue

Is not to die

Increasingly , the audience for these books was women, rather than artisans- women who were becoming more literate (Brown, 2004, 116). Many noble women were getting together to work on projects from these books, and even set up informal schools through their own homes (Brown 2004). The European markets were clearly starving for delicate laces when you see this volume of people making lace at home, and the professional market not being adversely affected. The patterns I have used for this project are from Volume II of Cesare Vecellio’s Corona delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne, which was originally printed in January of 1591.

Materials

For this project I used a large eyed, sharp embroidery needle, my pattern, and 2 different weights of linen threads. Many sewing needles and pins from this period are made of brass in a range of qualities and thicknesses. While I did try a reproduction brass needle and it worked well, I did find it difficult to consistently weave thread ends back into the lace using the period needle. Unlike my 16th century counterparts, I chose not to rip the pattern page out of my pattern book and used modern technology to make a copy of the pattern. I then covered the printing with clear tape to keep the modern toner from lifting off the page to make my lace dirty, and attach it to a thicker piece of watercolor paper to more closely match the weight of period parchments. After reviewing the surviving pieces of 16th century lace on the Metropolitan Museum’s website, I chose to use “z twist” linen thread as they had in the period. Strictly from a fiber working point of view, the linen was easy to find through lace supply shops, and it keeps a crisper line than silk threads do while producing lace.

Process

When working any design in punto in aria it is important to start by couching your foundation cords to the paper pattern to be produced. These cords will create the framework that you will encase and build from as you create your lace. Major elements should be laid out and couched down. Your foundation cords should be thicker than your working threads. This portion of the process is one of the differences between this lace style and reticella. In reticella you are working within previously woven fabrics and taking away some of the weaving to create room to do lace work.

Once the cords are laid you can start filling in your lace with the stitches you find appropriate to the design. The extent laces found online at the Metropolitan Museum of Art show buttonhole edging stitches, button hole filling stitches, and wrapped edges as popular working stitches for punto in aria and reticella lace.

Laying cord at the beginning of the piece for every punto in aria design element would create a bulky piece of lace and was not considered an attractive aesthetic until after our period. To create individual design elements and flourishes off the main framework you would create an arm. Using your working thread as you cover and fill out your design, the working thread is used as an offshoot line or loop which is anchored back to a foundation thread and worked over using the appropriate stitches to the lace maker’s design. These nearly detached design flourishes create the characteristic organic feeling of punto in aria which differentiates a completed piece from other styles.

Wearing and Care

Lace cuff such as these are a great luxury and were specifically very popular in Venice where Cesare Vecellio lived in the late 16th century. With so many young women in Venice being painted with intricate lace cuffs on their sleeves you must wonder if they were showcasing their family’s wealth, her good health, talents, and virtuous nature for potential suitors.

While there are no remaining sleeves with lace cuffs attached in museums, there are a few reasonable explanations on how these accessories were worn. These cuffs may have been sewn to the sleeves using large stitches and basic home sewing thread to keep them in place, while still giving the owner the option to remove them and place them on a different garment later. My preferred way of wearing lace cuffs is using dressing pins worked through openings in the lace to attach the cuffs to my sleeves. Using this method, the cuffs can quickly be taken on or off depending on the activity I am doing.

Many laces were attached to body linens and washed frequently. Laundresses were known to make lye soap using wood ashes and water mixed together and filtered through a towel to catch debris. Whites would then be dried in the sunlight on grasses to allow the sun to bleach them clean again. If this was not enough to whiten the linens, they could be bleached chemically. A common recipe for making bleach involved collecting human urine and allowing it to turn into pure ammonia (Sim 2010). I have not used any of these practices first had on this project. I live in an apartment and I am ill equipped to take on such an experiment currently.

Conclusions

While the actual stitches used to create punto in aria are simple to master, executing the designs with little to no over stitching is a challenge even for an accomplished lace maker or embroiderer. While machine made laces have overtaken the market and made lace readily available to all, they cannot achieve the complex, non –repeating, and unique patterns lace makers did in the 16th century.

References

Brown, Patricia Fortini (2004). Private Lives in Renaissance Venice. Londone: Yale University Press.

Landini, Roberta Orsi. (2011). Moda a Fireneze 1540-1580: Cosimo I de’ Medici’s Style. Fireneze: Mauro Pagliai Editore.

Preston, Doris Campbell. (1984). Needle-Made Laces and Net Embroideries. New York: Dover Publications.

Sim, Alison. (2010). The Tudor Housewife. Stroud: The History Press.

Vecellio, Cesare. (1988). Pattern Book of Renaissance Lace: A Reprint of the 1617 Edition of the “Corona delle Nobili et Virtuose Donne.” New York: Dover Publications.

Vinciolo, Federico. (1971). Renaissance Patterns for Lace, Embroidery and Needlepoint: An Unabridged facsimile of the “Singuliers et nouveaux pourtricats” of 1587. New York: Dover Publications.

Comments

Post a Comment